As Covid-19’s Omicron variant is pushing some school districts back into distance learning, teachers may be frustrated at the return of video meetings. However, imagine if video wasn’t as ubiquitous as it is today.

I contend that video technology helped to save education during the pandemic, and therefore should not be abandoned. As years of research from Harvard University has shown, the benefits of capturing and sharing videos to support preservice teachers, new teachers, and instructional coaching are far too great.

While a districtwide system dedicated to recording, annotating, and sharing video may sound like it would require a big budget, teachers can get started using just their cell phones. The evidence is all around us. From TikTok to Instagram to Snapchat, students are perfecting complex dances, learning, and showcasing their skills with musical instruments, teaching each other about climate change, and more.

That trend isn’t limited to young people. Educators are using video apps and tools to share lesson ideas, best practices, and classroom instruction. They record themselves, self-reflect, observe, and learn from each other. It’s all about growth.

Here are three suggestions for how educators can leverage video for years to come.

Teacher preparation

The pandemic forced teachers to broadcast videos to students who were at home. While this may have worked as a temporary solution, preservice teachers were not as fortunate.

Remote learning meant classrooms were shut down, with preservice teachers not only unable to be in schools, but also unable to observe more experienced teachers. As many teachers will attest, observing experienced teachers is critical to their development. This situation presented professors in teacher preparation programs with yet another challenge.

LaGrange College in Georgia was well-equipped to overcome this obstacle. Its teacher-preparation program had already been using video-based feedback for seven years. Dr. Rebekah Ralph, instructor of educational technology and EdTPA coordinator, pivoted to using video to support teacher candidates who had little to no interactions in the field.

During pandemic-induced shutdowns, Ralph provided feedback to preservice teachers from her back porch. As she recalls, she and her team “were able to support preservice teachers by continuing our observation and coaching models through the use of video when the school systems were not allowing visitors in the building. Our preservice teachers also were able to see a variety of teaching strategies used by their peers in diverse school settings as they shared, commented, and reflected on their teaching and the teaching of others.”

Mentoring and teacher induction

Research tells us that new teachers most often leave the profession in the first few years because they don’t feel supported. While mentor and induction programs have traditionally been effective, in the current environment, instructional coaches with districtwide responsibilities have been unable to visit classrooms frequently enough. The stress of teaching during a pandemic has amplified the problem.

Teachers who have entered the profession in the past 18 months only know chaos and uncertainty. As a result, and with an increasing shortage of teachers in the pipeline, education leaders like Kenya Elder, Executive Director of Teaching and Learning for Georgia’s Douglas County School System, have sought new ways to support new hires. This year, Douglas County onboarded 76 teachers “who were not only new to our district but also new to the teaching profession. This specific group of teachers joined us as we were enrolling and welcoming 26,000 students back to in-person learning.”

The problem, as Elder saw it, was, “How do we effectively and consistently connect our Induction Coaches to these teachers?” Their solution was to set up a structure that focuses on video observations “that are safe and non-evaluative.” So far, she says, this approach “is resulting in trusting relationships between teachers and coaches.”

Instructional coaching and observation

MSD Decatur Township in Indiana has been using video to support instructional coaching for about five years as part of the Empowering Educators to Excel (E3) TSL grant project.

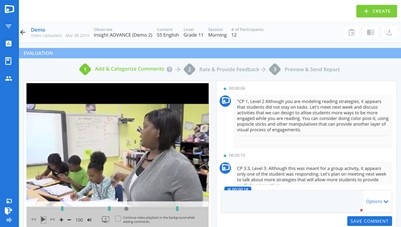

Assistant Superintendent Dr. Stephanie Hofer and the district’s instructional leadership team started by asking teachers to record 10 minutes of their practice in order to encourage self-reflection. Eventually, this led to teachers sharing videos with peers and mentors for feedback. As teachers and instructional coaches became more comfortable with video, Dr. Hofer said, “We started using it more because it was actually giving us more value than anything else we were doing.”

When the pandemic arrived and physical classrooms shut down, the district had to make a choice about how to best support teachers. They decided to double-down and increase the use of video coaching—but they were met with a new challenge. According to Dr. Hofer, “We weren’t sure how we were going to evaluate our teachers or get evaluations completed. We decided to give teachers the option of recording themselves and uploading their lessons—and we’re still giving them that choice.”

The district’s several years of implementing video coaching had built a culture that enabled it to push through a difficult period. Dr. Hofer said that the pandemic “…was the catalyst for our district to go all-in on video coaching and begin using asynchronous video for teacher evaluations with the full support of our teachers union.”

Despite how uncomfortable video can be at times, the benefits are clear. It’s a tool that can help teacher candidates, new teachers, and veteran teachers improve practice, while also increasing the reach of mentors and instructional coaches. There’s never been a more important time to support teachers, and video can play a vital role.